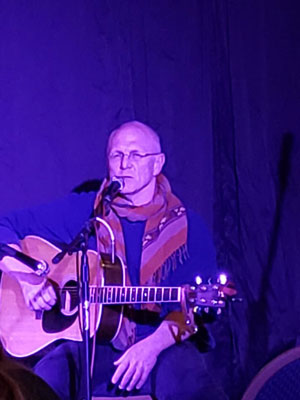

As frontman and chief songwriter/lyricist for 80s/90s seminal Pittsburgh rock band, Little Wretches, Robert Wagner rode a wave of local notoriety that led the band to the forefront of the underground music scene. The Little Wretches were founded as a folk/punk band by Robert (guitar) and his brother, Chuckie (violin). The “classic” Mach 2 era of Little Wretches included Ed Heidel (bass), Chris Bruckhoff (percussion, wind instruments, backing vocals) and Bob Goetz (guitar), rounded out by Dave Mitchell (drums), Mike Michalski (bass) and Ellen Hildebrand (electric guitar.) This rock edition of the band performed regularly and helped the band build its massive following in Pittsburgh. Michalski, Mitchell and Chuckie Wagner left the band, effectively ending.

Mach 3 began with the addition of David Losi (keyboards) and Mike Madden (drums.) When Madden couldn’t tour, drum programmer Gregg Bielski took over. When Ellen switched to bass guitar, this version of The Little Wretches entered the studio. They recorded two albums, with Angelo George playing drums and Jon Paul Leone playing guitar on a third. National press, attorneys, managers, and publicists came calling, as did life’s obligations, and the Little Wretches disbanded in the late 90s.Robert Wagner continues to perform at coffeehouses and small clubs. A Master’s Degree holder, Wagner also counsels abused, neglected, traumatized and court-adjudicated youth. He is the co-founder of The Calliope Acoustic Open Stage, an event that has lasted 15+ years. He has also recorded and released two new albums in 2020: Undesirables and Anarchists and Burning Lantern Dropped In Straw.

- Can you tell us a little bit about where you come from and how you got started making music?

Robert Andrew Wagner: I represent the Eighth Most Important City in the History of the World—PITTSBURGH, Pennsylvania. Historians and anthropologists debate the top seven, a lot of controversy there, you know, Jerusalem, Athens, Rome.

That academic community, they get into some contentious spats over the topic, but the weird thing is that there is consensus on Pittsburgh’s position. It is universally agreed that Pittsburgh is the eighth most important city in the history of the world, and I’m proud to be able to say that I grew up in a housing plan on a hill above a long-closed coal mine outside of Pittsburgh.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition. The French and Indian War. The Whiskey Rebellion. The Pittsburgh Crawfords. The Homestead Grays. Carnegie Steel. George Westinghouse. KDKA Radio. Billy Strayhorn. August Wilson. Billy Conn. Gene Kelly. The Little Wretches. Need I continue?

I started making music by taking scraps of plywood, pieces of two-by-fours, tacks and rubber bands and trying to make a guitar. My ninth birthday present was a Harmony acoustic guitar and a guitar-lesson, and my thirteenth birthday present was a Gibson Melody Maker that cost my mom fifty dollars. I play that guitar to this day.

Flash forward.

When I was in college, I was diagnosed with what was at the time a deadly form of cancer. I was lucky to be under the care of Doctors Samuel Jacobs and Ronald Stoller, two guys in tune with the latest research. They got me onto an experimental chemotherapy regimen that proved to be successful.

All I had ever wanted to do was write and play music. Imagine having to face eternity with the knowledge that you hadn’t pursued your greatest love.

John Creighton, my best friend and roommate, visited me every single day while I was in the hospital. We’d become friends through radical politics, but it turned out that he was the best musician I would ever know. One night, we looked at each other and said, “We need to start a band.”

- Have you had formal training or are you self-taught?

Robert Andrew Wagner: I don’t think there is such a thing as formal training for what I do. I took guitar lessons. For writing, I went to the University of Pittsburgh, a school with a powerful writing program. In that regard, I learned how to critique myself. I learned the protocols of practice, revision, woodshedding, workshopping, that kind of thing.

The band that John Creighton and I started, NO SHELTER, was kind of like an apprenticeship without a master. It was an apprenticeship based on self-directed learning. When I finally came to understand what I’m good at, what I’m capable of, I started The Little Wretches.

The Little Wretches, though, has always been a very “outsider” type of thing, and the keys to our success as a band and my personal success has more to do with survival skills than with instruction. Refusing to quit. Belief. Faith. Grit. Perseverance.

Dave Losi sings a song on our BEYOND THE STORMY BLAST album called FIVE TROUBLE. He quotes an inscription from the Wright Brothers Memorial in Kill Devil Hills, “Dauntless Resolution and Unconquerable Faith.”

Ain’t nobody I know can give lessons on dauntless resolution and unconquerable faith. I can’t even claim to be self-taught. Where that comes from, who knows? But I thank God for it.

- Who were your first and strongest musical influences that you can remember?

Robert Andrew Wagner: Me, my sister, and our cousins, were very close. We spent a lot of time in each other’s homes, and our playrooms always included a little turntable and boxes of 45 rpm records. We were always listening to music.

We listened to The Beatles. The Monkees. Petula Clark. The Mills Brothers. Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass. The Platters. Tom Jones. Glen Campbell. Lawrence Welk. Johnny Cash. Hee Haw. The Smothers Brothers. The Ames Brothers. The Sons of the Pioneers. The Doors. The Beach Boys. The Hollies. The Kinks. The Sonny and Cher Show. The Sound of Music. South Pacific. Jimmy Pol’s Polka Party. Nat King Cole. Perry Como. Dean Martin. Dolly Parton and Porter Wagoner. Simon and Garfunkel.

For us, music was beyond genre, beyond generation. Catchy beats. Catchy melodies. Memorable lyrics.

- What do you feel are the key elements in your music that should resonate with listeners?

Robert Andrew Wagner: I can’t allow myself to think about that. Obviously, I have no idea what resonates with listeners. I know what resonates with me.

I don’t want to alienate or freak people out, but I hate when church-people and artists use the language of marketing and sales, but I attended a “purpose-finding” seminar led by Reverend John Stanko, and he suggested that people should have a “personal mission statement.” You know how nonprofits have mission statements? He suggested that we do the same.

Over the years, I’ve come up with three.

Number one is from Lou Reed, “I’ll be your mirror, reflect what you are, in case you don’t know.” That line should be every artist’s mission statement. I want you to see yourself in my songs. Maybe that will resonate.

Another comes from Ian Hunter, “I want to weave you in words, I want to paint you in verse, I want to leave you in someone else’s dreams.” I want my songs to create characters so impactful that you feel like you have known them all your life. I want you to wake up thinking about somebody, and the more you think about it, you realize that person you were dreaming about was someone from one of my songs. Maybe that will resonate.

Lastly, I came across this line from the Prophet Isaiah, “The Lord God has given me the tongue of a teacher that I may be able to speak a word in season to him that is weary.” I want those who are weary to hear my songs and know that they are not alone. And knowing they are not alone will give them renewed strength, grit.

Look, I want to have a hit as much as any other songwriter, but mostly I want to reach those desperately broken people who, like me, have had their lives saved through music. Music saved my life. Maybe mine will save someone else’s.

- For most artists, originality is first preceded by a phase of learning and, often, emulating others. What was this like for you? How would you describe your own development as an artist and music maker, and the transition towards your own style?

Robert Andrew Wagner: I didn’t have sufficient musical or social skills to emulate anybody. I was a loner. I wasn’t good enough to be in a cover band. I got the whole process backwards. Eventually, I got good enough to interpret other peoples’ songs by writing and playing my own.

I understand what you’re asking though.

When I was fifteen, living in a room above my grandmother’s garage (she called it “the cold room), I used to scribble lyrics in pencil on a piece of cardboard. I didn’t even have paper. And I’d make little notes that this section should be sung in the voice of Marc Bolan of T. Rex, another section in the voice of John Lennon, another section in the voice of Bowie from the HUNKY DORY album.

When I heard Lou Reed, Bob Dylan and Patti Smith, it wasn’t that I wanted to emulate them as much as I recognized that it is indeed possible for someone like me to sing in a rock’n’roll band. If they can do it, so can I.

In my corner of the Punk scene, emulating people was anathema. Find your own voice. Create your own vehicle. The Little Wretches was my vehicle.

Fast forward. I’m singing in a rock’n’roll band, but I keep feeling like I’m not getting my point across. Whatever I’m doing is getting swallowed up in the noise. I’m a conversational lyricist singing through p.a. systems set up for screaming hardcore singers. People can’t understand a word I’m saying.

How can I make music that rocks but also gets my story across? Jonathan Richman. Michelle Shocked. Peter Himmelman. The earliest version of The Little Wretches was modeled after Jonathan Richman from his “Jonathan Sings.” After seeing Michelle Shocked and Peter Himmelman, I had a model for doing solo-shows and acoustic shows.

- What’s your view on the role and function of music as political, cultural, spiritual, and/or social vehicles – and do you affront any of these themes in your work, or are you purely interested in music as an expression of technical artistry, personal narrative and entertainment?

Robert Andrew Wagner: I have a background in radical political activism also religious evangelism. The bad news is that they are identical in their psychology. The browbeating. The guilt. The Us-versus-Them scenario. Marxism is Catholicism. The REVOLUTION is HEAVEN. The Maoist practice of Criticism/Self-Criticism is the Catholic sacrament of Reconciliation.

I love hymns. I love Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie and Phil Ochs, but otherwise, I absolutely DETEST “message” music. I absolutely DETEST the practice of preaching to the already converted. I absolutely DETEST the practice of telling people what they already believe. In the church, there is a place for praise-and-worship music. In politics, there is a place for propaganda and agitation around specific issues. I get it. But call it for what it is. It is praise-and-worship. It is agit-prop. It is the art of rhetoric, but it is not the art of poetry, music or songwriting.

Your real message is the way you live your life.

I detest the arrogance of people who think they are engaging in “consciousness-raising.” Who are YOU to think YOUR CONSCIOUSNESS is higher than MINE? What makes you think so highly of yourself? What makes you think you are enlightened and others are in the dark?

That being said, I am a teacher. In my tradition, we teach through stories. I tell stories through songs. I have a master’s degree in Instruction and Learning. I am a proponent of self-directed learning, voluntary learning, non-compulsory learning, unschooling. I understand that what I think I am teaching may have nothing at all to do with what you are learning.

I ain’t no preacher. I ain’t selling you nothing. I ain’t trying to convince you of anything. But I am trying to act in accordance with my beliefs.

I believe that eternity exists, God is good, and life is precious. In my tradition, we believe that people are made in the image of God. In my songs, I try to honor my father and mother, to love my neighbor as myself, and to reflect as honestly as I can the lives of the people I love. And in the process, I sometimes put the spotlight on things the religious and political activists would rather you not notice.

- Do you ever specifically write a song with musical trends, formulas or listener satisfaction in mind, or do you simply focus on your own personal vision and trust that it will be appreciated by a specific audience?

Robert Andrew Wagner: I’m from Pittsburgh. In my lifetime, we’ve always been five to seven years behind the trends. Trend-chasing is futile in Pittsburgh unless you enjoy being a big fish in a small pond.

I look at what is timeless, what is enduring.

I study the form. Think of it as the “grammar” of song. There is an aesthetic, a sensibility, a feeling that this belongs but that doesn’t belong, a sense of proportion, a sense that if we get it right, it will sound timeless. That’s what I want—music that will sound fresh twenty years from now. And if you listen to stuff I recorded twenty years ago, you will concede that I was successful.

But I also focus on being productive. What can I create with the tools at my disposal? What if I don’t have the ingredients the recipe calls for? What? Should I go hungry? No. I will figure out how to make something tasty with the ingredients I have.

Let’s face it. For most people, music is like a cigarette, a cup of coffee, a blunt or a beer. People use music to regulate their moods. That’s the brutal truth. It’s a self-medicating feel-good culture.

But where I’m from and what I’ve been through, your drugs don’t work on me. Your feel-good music makes me feel bad. Your uplifting music leaves me feeling like an ugly freak of nature because it doesn’t lift me up, it beats me down.

If you’re a musician, you have to choose. You’re either a healer or a dealer. And even if you think you’re a healer – that which can heal can also be abused.

So if my answer hasn’t been sufficiently evasive, let me add one more level of weirdness. There’s a story in the Bible about disciples being sent out to spread the message. “But what are we supposed to say?” Don’t worry what you’re supposed to say. When it’s time for you to speak, the words will be given to you.

So I guess the short answer is that I write for a very specific, highly critical and discerning audience that exists only in my imagination. I’m striving for an ideal. When I get close to it, it doesn’t much matter to me how people respond. It’s like watching gymnastics in the Olympics. I know when I nailed it. I know when I stuck the landing.

- Could you describe your creative processes? How do you most often start, and go about shaping ideas into a completed musical piece? Do you usually start with a beat, a narrative in your head, or a melody?

Robert Andrew Wagner: I’ve got a wheel over here. I’ve got something that might serve as an axle over there. Here’s a gear. There’s a lever. I use the analogy of the songs being vehicles. I suppose the world is my junkyard, and I find pieces of machinery everywhere.

The truth is, I rarely have the tools I need to articulate what exists in my imagination. I modify what I imagine to the design made possible by my resources.

I may start with a lyric or a chord-pattern, or a bass-line, or a melody.

This is going to sound nasty, but when I’m listening to my peers, I ask, “If that idea had occurred to me, what would I have done with it?” Often, forgive me, I say, “If I’d have had that idea, I’d have discarded it.”

I don’t know where the ideas come from. And yes, I have on occasion sat down thinking, “I need to write a song,” but nothing is there. And other times, the ideas just flow, and songs emerge in almost finished form.

- What has been the most difficult thing you’ve had to endure in your musical career, or life, so far? And how did you overcome that event?

Robert Andrew Wagner: I’ve often had the feeling that I’m running out of time, that there is something I am meant to do, haven’t done it yet, and what if I don’t accomplish whatever it is?

I was an abandoned kid. So I have trust and attachment issues, shall we say. Then to compound that, I know a lot of dead people. You don’t want to hear the list.

I mentioned earlier that before John Creighton and I started No Shelter, I was diagnosed with cancer. My mom, the mom who’d abandoned me and had not seen me in years, learned of my condition and came to see me every single day in the hospital. She spent 24-hours a day running from hospital to hospital, caring for loved ones, totally selfless. I’d been so angry with her and felt like I needed to punish her. No matter what she did to let me know that she loved me, I had to brush it off and extract my pound of flesh.

Unless it served me somehow. For example, she invited No Shelter to use her garage as a practice space. She came to our first gig, got embarrassingly drunk, and I think I saw her one more time before she died later that summer. We’ll never know for sure if it was suicide, murder or an accidental death.

I coped with it mainly through denial. I’d tell myself that every day was just like any other day, and this would be one of those days in which I wouldn’t see my mother. And tomorrow would be another one of those days. And the day after that.

That’s the pattern of my life. And I’ve lost a lot of people. It’s one of the reasons I have a good memory. As I’m experiencing something, I’m not really feeling anything. I’m observing myself, storing away all the sensations to be processed later. I need a lot of alone-time for processing. And some experiences, I’ll stash them away for months and years before allowing myself to feel them.

It can make for some pretty powerful songs, all that pent up sensation. Your readers are going to find this all kind of heavy and ponderous, but for me it’s just a fact of life.

The most difficult thing for me to endure is that the experiences that have made me who and what I am are experiences that are not polite to talk about, experiences that sometimes make others uncomfortable. So I have to choose between being who I am or walking around in some kind of disguise, pretending to be just another person, just like you. But I ain’t just like you.

I haven’t overcome anything. I’ve endured and pushed forward. Put your shoulder to the plough and don’t look back.

- On the other hand what would you consider a successful, proud or significant point in your career so far?

Robert Andrew Wagner: Well, what I just told you IS my most successful thing. The unity of opposites. I try to put my shoulder to the plough and don’t look back. The people I’ve lost, I try to honor them through my songs.

I was talking earlier about mission statements. I quoted Lou Reed, “I’ll be your mirror, reflect what you are.” The thing about images and reflections is that every picture needs a frame and every story needs a context.

What is my context? I feel like I exist in some kind of anomaly of time. Eternity is unfathomable, but I’m trying to see things from the point of view of eternity. John, Ed, Chuckie, David, my mom, my dad, my grandmother, the people I’ve lost, remember what I said about denial? It’s like they’re not really gone. They’re here with me at all times. Kinda deep. I hope it isn’t too creepy for you.

- How would you describe the sound and style of your project “Undesirables & Anarchists” to any potential new fan?

Robert Andrew Wagner: I’m surprised and flattered by what has been written about UNDESIRABLES & ANARCHISTS. Today, I saw a review that compared The Little Wretches to The Who. It said one of our songs sounded like a long-lost classic.

We’re generally called “folk rock,” but we sound nothing like what you hear on your public-radio Sunday morning folk show. Nothing against Puff, the Magic Dragon, but I got no time for Peter, Paul and Mary. The Little Wretches are as folk as a Lomax field-recording. We are telling the stories of our people. Real rap, as they used to say.

One person said we sounded like a cross between The Clash and The B-52s. A few folks have tossed around Paul Westerberg’s name. Mott the Hoople.

UNDESIRABLES & ANARCHISTS was pretty much a live-recording. But on our next album, I’m going to be playing mostly acoustic guitar.

It’s possible that new fans will be disappointed when they dig into our catalogue and discover that our albums have such a wide range of sounds and styles. Oh, well.

But what I really think will happen is that a few people will dip into the catalogue and, over time, find themselves acquiring everything we’ve ever done.

As a fan, that’s how I am. I have everything ever done by my favorite artists.

- Where did the original idea and inspiration behind the compilation of “Undesirables & Anarchists” come from, and is there an overarching theme and message you’re trying to send out via the project?

Robert Andrew Wagner: The title comes from the song, ALL OF MY FRIENDS, the lines, “All of my friends are on somebody’s list of undesirables and anarchists / It’s not even safe to admit that you’re one of my friends.” So far in this interview, I’ve said a lot about my life, my beliefs, but I think I also said that what people hear may have nothing at all to do with what I think I am saying.

It’s not like we started with a title or a theme and built around it. We started with a batch of songs that seemed to form a coherent whole. It sounded right. It felt right. After the fact, we can look at it, examine it, and see how and why the pieces work together.

I’ve got a background story for every line of every song. But that’s just a conceit for me. For you, who knows? I wish I knew what it would be like to hear this album for the first time.

But picking it apart now, I see how the songs are consistent with the name of the band. We’re The Little Wretches, right? As in, “Amazing Grace, how sweet the sound, to save a wretch like me.” As in The Beatitudes, “Blessed are the meek, the poor in spirit, the reviled and persecuted.” As in wandering all night in a rat’s maze of roads because they’re fighting at home. As in, “If this is good enough for everybody else, how come I feel so defiled?”

“Carving a niche between the dust and the ether.” That’s us. That’s The Little Wretches. We ain’t got a home in this world. We didn’t choose it. We didn’t ask for it. That’s just the way it is.

The songs are loaded with faith, grace, and hope.

- Did you use any particular sounds and/or recording techniques on these songs, and what were the main compositional, performance or production challenges you came across in completing this recording?

Robert Andrew Wagner: We won a small amount of studio time for participating in an event that I will not mention that was sponsored by a number of recording studios in the Pittsburgh-area. I made appointments with the studios.

I had never met Dave Granati, the owner of the studio, but I liked him immediately. He and his brothers had toured as the opening act for Van Halen, for crying out loud. I explained to Dave how I like to work, and he got it immediately.

See, when you go into a studio, it takes an eternity to tweak the sounds. You spend six hours setting up, then you do some recording, then you gotta tear down for the next band to come in. Next session, six more hours of set up.

My thing is, once you got the stuff set up, once you got the sound you’re looking for, KILL IT. GO FOR IT. DO IT. The Beatles recorded two years’ worth of releases in one big session. Dylan.

Record the rhythm tracks live. Overdub the vocals. Double the electric guitars with acoustic guitars. Lay down the solos. Lay down the percussion. If you played it right, it mixes itself.

Dave Granati grasped to concept. If he was skeptical, he didn’t let it show. He said that if we could record without a headphone mix, just set up like a live show, he could be recording us by the time we were finished setting up.

Most studios mic each piece of the drum kit separately and spend hours pound-pound-pound, tap-tap-tap. Dave started with the room sound. He used overhead mics. Yes, he put a mic on each drum and each amp, but he used those mics to fill out and lend definition to the sound. Mostly, he captured a very hot band playing exactly the way it played live.

We intended to “punch-in” to correct mistakes. But we didn’t make any mistakes. We may never again play as well.

- Where do you record, produce and master most of your work? And do you outsource any of these processes or are you totally self-sufficient?

Robert Andrew Wagner: Gregg Bielski, former member of The Little Wretches and an incredibly prolific noise, ambient and industrial artist, pointed me to Tom Dimuzio for mastering. Tom’s company is called Gench. I’ve heard Tom as a “noise artist” at places like the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Tom had seen and heard The Little Wretches in the very early days. He’s just one of those amazing people that we were fortunate to be able to work with.

I can make demos at home, but I’ve spent so much time listening to bootlegs and unauthorized recordings that I don’t trust myself. I work very fast, and I need to be able to trust a highly competent engineer to dial us into something in the ballpark of industry standards. And in my haste, every now and then, I need someone to say, “I know you can do better. Please do another take.”

I recorded a lot at Gregg Vizza’s Audiomation in Pittsburgh, but Audiomation isn’t around anymore. I did a few projects with Tom Hitt at Cycling Troll Studio in Erie. (Tom is in Idaho now. Tom’s brother, Jay Hitt, is one of my three favorite songwriters.) Rosa Colucci and I did WHEN IT SNOWS at Complex Variables, Michael Ketter’s studio, but Michael is in eternity now.

For the project we’re getting ready to undertake, we may go back to Dave Granati. Maybe not. Depends on how our rehearsals unfold.

- How essential do you think video and visual media is, in relation to your songs, and music in general? And do you have a video you’d like to suggest to fans watch?

Robert Andrew Wagner: Are you trying to hurt my feelings? I’ve been able to recruit great musicians to play with The Little Wretches, but we’re totally lacking when it comes to video. These professional visual artists are such mercenaries. We used to have to spend as much on the artwork as we spent on the recording. We released one album without a cover, the eponymously titled THE LITTLE WRETCHES, a.k.a “The Nude Album.”

I am NOT a visual artist. I hate bad videos. I hate stupid videos. I hate band photos. But I appreciate beautiful imagery. I appreciate striking imagery. I appreciate montage and editing. Eisenstein. Vertov. Alekan. Orson Welles. Spike Lee.

PLEASE PLEASE PLEASE PLEASE PLEASE. If you are or know of a talented filmmaker who does with the camera what we do with songs, send that person our way.

Our songs are cinematic. We NEED a real filmmaker. We need a down-and dirty, bubblegum and cellphone-wielding kid with something to prove. Or Spike Lee.

That being said, if you go on YouTube and do a search for The Little Wretches, there are some very good live shows. Chuck Parish used to set up a video camera at gigs. I didn’t understand the value of what he was doing at the time, but I am now so grateful he captured that stuff. The Little Wretches at The Decade. The Little Wretches at Moondog’s. The Little Wretches at the El Dorado. One stationary camera, like a Warhol film.

- Do you have a favorite motto, phrase or piece of advice, you try to live or inspire yourself by?

Robert Andrew Wagner: Ouch. Now that you’re putting me on the spot, I can’t think of any.

Peter Fonda’s Captain America in EASY RIDER, “You do your own thing in your own time. You should be proud.”

The Rolling Stones’ Ruby Tuesday, “Lose your dreams and you will lose your mind.

Popeye the Sailor Man, “I yam what I yam.”

Romans, 8:31, “If God is for us, who can be against us?”

Viv Savage in THIS IS SPINAL TAP, “Have a good time ALL the time.”

- Studio work and music creation, or performing and interacting with a live audience, which do you prefer?

Robert Andrew Wagner: LIVE. I wanna play in your living room. I wanna play on your porch. I wanna sit on your bedroom floor and play for you. I want to come to your town, your church, your school, your abandoned warehouse, your folk club, your punk club, your gallery.

I might say otherwise if I could step outside of time and space and get John Creighton, Dave Losi, Ellen Hildebrand, Ed Heidel, Chuck Wagner, Rosa Colucci and Jon Paul Leone together with unlimited studio time. Put Mike Madden behind the drum kit. Have David Flynn mixing the drinks. Mark Pinto and Gregg Bielski in the next room with portable cassette recorders.

- If the name ‘Robert Wagner’ came up in a conversation among music fans, alongside which other artists would most you like to be associated with in that conversation?

Robert Andrew Wagner: Steve Earle. Phil Ochs. Ray Davies. The Dream Syndicate. Ian Hunter. Ray Wylie Hubbard. And my homies, Jack Erdie, Jay Hitt and Nate Gates.

- Do you have a personal favorite track amongst your compositions that has a specific backstory and/or message and meaning very special to you?

Robert Wagner: I have quite a few, actually, and several of them are going to be on RED BEETS & HORSERADISH, the album we’re getting ready to record. The songs generally involve characters that are old, crazy, sick, but full of humor, grit and resilience.

I have a song called DUQUESNE. My mother graduated from Duquesne High School. Every corner in Duquesne is occupied by a building that used to be a church, each for a different ethnicity. When the steel industry in the region closed, everybody in Duquesne who could afford to relocate moved to greener pastures. The people who remained were either too sick, too poor or too stubborn to leave. Those, and the predators who know how to siphon money from the sick, poor and stubborn.

No Shelter performed a version of DUQUESNE at our very first show, and I’ve been revising and reworking the song all of my adult life.

The narrator slips back and forth from the third to the first person. The central character is a retired woman, an immigrant from what had been known as Czechoslovakia. She lives in Duquesne but still gets up and rides the bus into downtown Pittsburgh every day as though she still has a job. Instead of going to work, she sits in a church all day, then takes the bus home. A portrait. A character-study. A landscape. A lot of history and life embedded in a song.

- What do you find most rewarding about what you do? And do you have a specific vision or goal set in your mind that you would like to achieve in the near future?

Robert Andrew Wagner: When I was a kid, I heard a song called “DOMINIQUE” sung in French by “The Singing Nun.” The English translation said, “Never asking for reward, he just talks about the Lord.” I suppose I took the song too literally. Somehow, it processed in my young mind as, “It is wrong to ask for reward.” Kind of like the Christmas carol, The Little Drummer Boy. The only gift I have to offer you is this. Please, let me play for you.

Doesn’t that sound so arrogantly lofty and pompous. Don’t you think you’re something, too good to think about rewards. Punk. Get real about yourself. But really, all I want is to wake up in the morning, thinking about where I am playing tonight. I have a lifetime of really good songs, and a whole world full of people that haven’t heard me.

So. What stands between me and that goal? I could use a good filmmaker. I need a booking agent. What I need to do, I cannot do alone. I dig it. There are artists who cut out the middle man and manage themselves, book themselves, the whole deal. And every penny they earn, they get to keep. That isn’t me.

The cool thing is that I know there are people that I haven’t met yet who will play pivotal roles in the story I’ve yet to live. A lot to be thankful for, and a lot to look forward to.

OFFICIAL LINKS: WEBSITE – FACEBOOK – SPOTIFY

More Stories

“Hay Zeus”, Heavy History: Ty Bru on Legacy, Layers, and Letting Go at 20 Years of MTTS

The Cosmic Factory on 15 Years of Psychedelic Alchemy and the Making of ‘Lab Grown’

Detroit Soul, Modern R&B Elegance: An Interview with Reggie Braxton